.jpg)

He married his first wife Dorothy Bonvillion in 1950, but they divorced in 1951. He was enlisted in the United States Marine Corps until his discharge in 1953. He was stationed in San Jose, California for his entire service.

.jpg) Jones' first hit came with "Why Baby Why" in 1955. That same year, while touring as a cast member of the Louisiana Hayride, Jones met and played shows with Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash. "I didn't get to know him that well," Jones said of Presley to Nick Tosches in 1994. "He stayed pretty much with his friends around him in his dressing room. Nobody seemed to get around him much any length of time to talk to him." Jones would, however, remain a lifelong friend of Johnny Cash. Jones was invited to sing at the Grand Ole Opry in 1956.

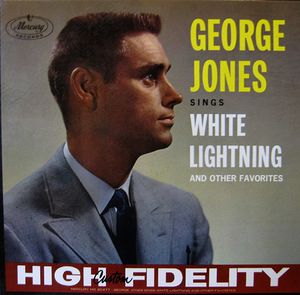

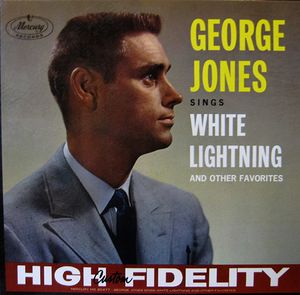

Jones' first hit came with "Why Baby Why" in 1955. That same year, while touring as a cast member of the Louisiana Hayride, Jones met and played shows with Elvis Presley and Johnny Cash. "I didn't get to know him that well," Jones said of Presley to Nick Tosches in 1994. "He stayed pretty much with his friends around him in his dressing room. Nobody seemed to get around him much any length of time to talk to him." Jones would, however, remain a lifelong friend of Johnny Cash. Jones was invited to sing at the Grand Ole Opry in 1956. In 1959, Jones had his first number one on the Billboard country chart with "White Lightnin'", ironically a more authentic rock and roll sound than his half-hearted rockabilly cuts. In the Same Ole Me retrospective, Johnny Cash insisted, "George Jones woulda been a really hot rockabilly artist if he'd approached it from that angle. Well, he was, really, but never got the credit for it." "White Lightnin'" was written by J.P. Richardson, better known as the Big Bopper. In I Lived To Tell It All, Jones confessed that he showed up for the recording session under the influence of a great deal of alcohol and it took him approximately 80 takes just to record his vocals. To make matters worse, Buddy Killen, who played the upright bass on the recording, was reported as having severely blistered fingers from having to play his bass part 80 times. Killen not only threatened to quit the session, but also threatened to physically harm Jones for the painful consequences of Jones' drinking. On the final vocal take used on the recording Jones slurs the word "slug", something he would mimic in live performances of the song along with using his southern drawl.

In 1959, Jones had his first number one on the Billboard country chart with "White Lightnin'", ironically a more authentic rock and roll sound than his half-hearted rockabilly cuts. In the Same Ole Me retrospective, Johnny Cash insisted, "George Jones woulda been a really hot rockabilly artist if he'd approached it from that angle. Well, he was, really, but never got the credit for it." "White Lightnin'" was written by J.P. Richardson, better known as the Big Bopper. In I Lived To Tell It All, Jones confessed that he showed up for the recording session under the influence of a great deal of alcohol and it took him approximately 80 takes just to record his vocals. To make matters worse, Buddy Killen, who played the upright bass on the recording, was reported as having severely blistered fingers from having to play his bass part 80 times. Killen not only threatened to quit the session, but also threatened to physically harm Jones for the painful consequences of Jones' drinking. On the final vocal take used on the recording Jones slurs the word "slug", something he would mimic in live performances of the song along with using his southern drawl.Jones signed with United Artists in 1962 and immediately scored one of the biggest hits of his career, "She Thinks I Still Care". His voice had grown noticeably deeper during this period and he began cultivating the singing style that became uniquely his own. During his stint with UA, Jones recorded tribute albums to Hank Williams and Bob Wills and cut an album of duets with Melba Montgomery, including the hit "We Must Have Been Out Of Our Minds".

Later years

In 1990, Jones released his last proper studio album on Epic, You Oughta Be Here With Me. Although the album featured several stirring performances, including the lead single "Hell Stays Open All Night Long" and the Roger Miller-penned title song, the single did poorly and Jones made the switch to MCA, ending his relationship with Sherrill and what was now Sony Music after 19 years.

His first album with MCA, And Along Came Jones, was released in 1991 and, backed by MCA's powerful promotion team and producer Kyle Lehning (who had produced a string of hit albums for Randy Travis), the album sold better than his previous one had. However, two singles, "You Couldn't Get The Picture" and "She Loved A Lot In Her Time" (a tribute to Jones' mother Clara), did not crack the top 30 on the charts as Jones lost favor with country radio as the format was altered radically during the early 1990s. His last album to have significant radio airplay was 1992'sWalls Can Fall, which featured the novelty song "Finally Friday" and "I Don't Need Your Rockin' Chair," a testament to his continued vivaciousness in old age. Despite the lack of radio airplay, Jones continued to record and tour throughout the 1990s and was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame by Randy Travis in 1992. In 1996, Jones released his autobiography I Lived To Tell It All with Tom Carter and the irony of his long career was not lost on him, with the singer writing in its preface, "I also know that a lot of my show-business peers are going to be angry after reading this book. So many have worked so hard to maintain their careers. I never took my career seriously, and yet it's flourishing." He also pulled no punches about his disappointment in the direction country music had taken, devoting a full chapter to the changes in the country music scene of the 1990s that saw him removed from radio playlists in favor of a younger generation of pop-influenced country stars. Despite his absence from the country charts during this time, latter-day country superstars such as Garth Brooks, Randy Travis, Alan Jackson, and many others often paid tribute to Jones while expressing their love and respect for his legacy as a true country legend who paved the way for their own success.

On February 17, 1998, The Nashville Network premiered a group of television specials called The George Jones Show, with Jones as host. The program featured informal chats with Jones holding court with country's biggest stars old and new and, of course, music. Guests included Loretta Lynn, Trace Adkins, Johnny Paycheck, Lorrie Morgan, Merle Haggard, Billy Ray Cyrus, Tim McGraw, Faith Hill, Charley Pride, Bobby Bare, Patty Loveless and Waylon Jennings, among others.

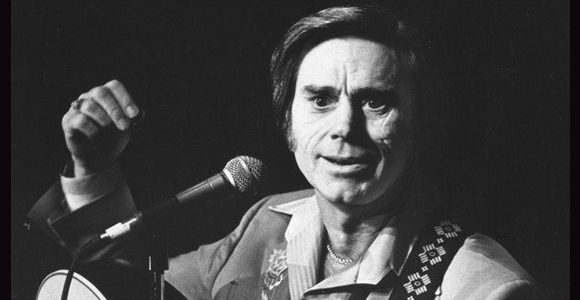

.jpg) While Jones remained committed to "pure country", he worked with the top producers and musicians of the day and the quality of his work remained high. Some significant performances include "I Must Have Done Something Bad", "Wild Irish Rose", "Billy B. Bad" (a sarcastic jab at country music establishment trendsetters), "A Thousand Times A Day", "When The Last Curtain Falls" and the novelty "High-Tech Redneck". Jones most popular song in his later years was "Choices", the first single from his 1999 studio album Cold Hard Truth. A video was also made for the song and Jones won another Grammy for Best Male Country Vocal Performance. The song was at the center of controversy when the Country Music Association invited Jones to perform it on the awards show, but required that he perform an abridged version. Jones refused and did not attend the show. Alan Jackson was disappointed with the association's decision and halfway through his own performance during the show he signaled to his band and played part of Jones' song in protest.

While Jones remained committed to "pure country", he worked with the top producers and musicians of the day and the quality of his work remained high. Some significant performances include "I Must Have Done Something Bad", "Wild Irish Rose", "Billy B. Bad" (a sarcastic jab at country music establishment trendsetters), "A Thousand Times A Day", "When The Last Curtain Falls" and the novelty "High-Tech Redneck". Jones most popular song in his later years was "Choices", the first single from his 1999 studio album Cold Hard Truth. A video was also made for the song and Jones won another Grammy for Best Male Country Vocal Performance. The song was at the center of controversy when the Country Music Association invited Jones to perform it on the awards show, but required that he perform an abridged version. Jones refused and did not attend the show. Alan Jackson was disappointed with the association's decision and halfway through his own performance during the show he signaled to his band and played part of Jones' song in protest.

On March 6, 1999, Jones was involved in an accident when he crashed his sport utility vehicle near his home. He was rushed to the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, where he was released two weeks later. In May of that year, Jones pleaded guilty to drunk driving charges related to the accident. (In his memoir published three years earlier, Jones admitted that he sometimes had a glass of wine before dinner and that he still drank beer occasionally but insisted, "I don't squirm in my seat, fighting the urge for another drink" and speculated, "...perhaps I'm not a true alcoholic in the modern sense of the word. Perhaps I was always just an old fashion drunk.") The crash was a significant turning point, as he explained to Billboard in 2006: "...when I had that wreck I made up my mind, it put the fear of God in me. No more smoking, no more drinking. I didn't have to have no help, I made up my mind to quit. I don't crave it." After the accident, Jones went on to release The Gospel Collection in 2003, which Billy Sherrill came out of retirement to produce. He appeared at a televised Johnny Cash Memorial Concert in 2003, singing "Big River" with Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson. In 2008, Jones received the Kennedy Center Honor along with Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey of The Who, Barbra Streisand, Morgan Freeman and Twyla Tharp. President George W. Bush disclosed that he had many of Jones' songs on his iPod. Jones also served as judge in 2008 for the 8th annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists' careers. and Rolling Stone named him number 43 in their 100 Greatest Singers of All Time issue. An album titled Hits I Missed And One I Didn't, in which he covered hits he had passed on as well as a remake of his own "He Stopped Loving Her Today", would be released as his final studio album. In 2012, Jones received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement award.

On March 29, 2012, Jones was hospitalized with an upper respiratory infection. Months later, on May 21, Jones was hospitalized again for his infection and was released five days later. On August 14, 2012, Jones announced his farewell tour, the Grand Tour, with scheduled stops at 60 cities His final concert was held in Knoxville at the Knoxville Civic Coliseum on April 6, 2013.

Jones was scheduled to perform his final concert at the Bridgestone Arena on November 22, 2013. However, on April 18, 2013, Jones was admitted to Vanderbilt University Medical Center for a slight fever and irregular blood pressure. His concerts in Alabama and Salem were postponed as a result. While there, Jones died in the early morning hours of April 26, 2013, aged 81, from hypoxic respiratory failure. Former first lady Laura Bush was among those eulogizing Jones at his funeral on May 2, 2013. Other speakers were Tennessee governor Bill Haslam, news personality Bob Schieffer, and country singers Barbara Mandrell and Kenny Chesney. Alan Jackson, Kid Rock, Ronnie Milsap, Randy Travis, Vince Gill, Patty Loveless, Travis Tritt, the Oak Ridge Boys, Charlie Daniels, Wynonna and Brad Paisley provided musical tributes. The service was broadcast live on CMT, GAC, RFD-TV, The Nashville Network and Family Net as well as Nashville stations. SiriusXM and WSM 650AM, home of the Grand Ole Opry, broadcast the event on the radio. The family requested that contributions be made to the Grand Ole Opry Trust Fund or to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

Jones was scheduled to perform his final concert at the Bridgestone Arena on November 22, 2013. However, on April 18, 2013, Jones was admitted to Vanderbilt University Medical Center for a slight fever and irregular blood pressure. His concerts in Alabama and Salem were postponed as a result. While there, Jones died in the early morning hours of April 26, 2013, aged 81, from hypoxic respiratory failure. Former first lady Laura Bush was among those eulogizing Jones at his funeral on May 2, 2013. Other speakers were Tennessee governor Bill Haslam, news personality Bob Schieffer, and country singers Barbara Mandrell and Kenny Chesney. Alan Jackson, Kid Rock, Ronnie Milsap, Randy Travis, Vince Gill, Patty Loveless, Travis Tritt, the Oak Ridge Boys, Charlie Daniels, Wynonna and Brad Paisley provided musical tributes. The service was broadcast live on CMT, GAC, RFD-TV, The Nashville Network and Family Net as well as Nashville stations. SiriusXM and WSM 650AM, home of the Grand Ole Opry, broadcast the event on the radio. The family requested that contributions be made to the Grand Ole Opry Trust Fund or to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.Jones was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Nashville. His death made headlines all over the world; many country stations (as well as a few of other formats, such as oldies/classic hits) abandoned or modified their playlists and played his songs throughout the day. The week after Jones's death, "He Stopped Loving Her Today" re-entered the hot country songs at number 21.

For the last 20 years of his life, Jones was frequently referred to as the greatest living country singer. Country music scholar Bill C. Malone writes...

For the two or three minutes consumed by a song, Jones immerses himself so completely in its lyrics, and in the mood it conveys, that the listener can scarcely avoid becoming similarly involved.

Waylon Jennings expressed a similar opinion in his song "It's Alright"..

If we all could sound like we wanted to, we'd all sound like George Jones.

The shape of his nose and facial features earned Jones the nickname "The Possum."